Sensitive and unbiased genome-wide profiling of base-editor-induced off-target activity using CHANGE-seq-BE – Nature Biotechnology

Development of a sensitive and unbiased biochemical method to measure base editor genome-wide activity

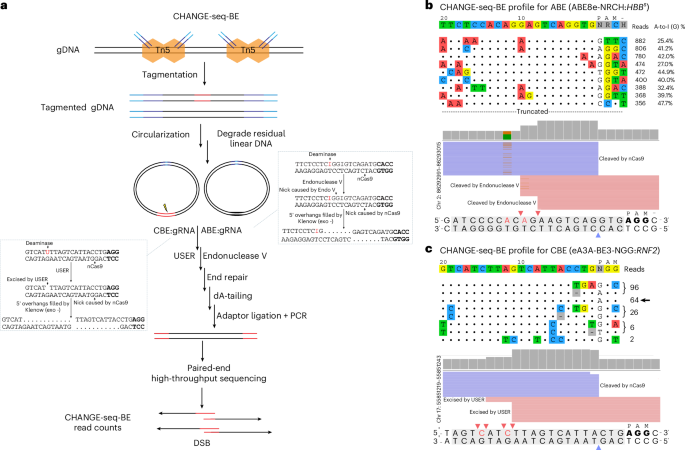

Motivated by a critical need for better methods to directly characterize the gRNA-dependent genome-wide off-target activity of base editors, we sought to develop a method that would be simultaneously sensitive, unbiased, sequencing efficient and straightforward to practice. We reasoned that CHANGE-seq could be adapted for base editors by treating purified, circularized gDNA with base editor RNP complexes and selectively sequencing base-editor-modified gDNA (Fig. 1a). First, linear gDNA could be circularized using our previously described CHANGE-seq Tn5 tagmentation-mediated approach20. Second, for ABEs, enzymatically purified gDNA circles could be treated with ABE RNP complexes to nick the target DNA strand and deaminate adenine bases to inosine (within the base-editing window) on the nontarget strand at on-target and off-target sites. Third, nicked and inosine-containing gDNA circles could be further processed with endonuclease V (ref. 21), which cleaves DNA adjacent to inosines to produce linear DNA with 5′ staggered ends. Similarly, for CBEs, circularized gDNA could be treated with CBE RNP complexes to nick the target DNA strand and deaminate cytosine bases to uracil on the complementary DNA strand. Uracil-containing gDNA circles could be further processed with USER enzyme (uracil-specific excision reagent), a mixture of uracil DNA glycosylase and the DNA glycosylase–lyase endonuclease VIII, which cleaves and removes uracil in the nontarget DNA strand to generate linearized DNA. The base-editor-modified linear DNA processed by endonuclease V or USER enzyme could be end-repaired and ligated to sequencing adaptors for selective high-throughput sequencing of base-editor-modified gDNA molecules.

a, Schematic of CHANGE-seq-BE workflow. Purified gDNA is tagmented with custom Tn5 transposome containing circularization adaptor DNA. Tagmented gDNA is circularized by intramolecular ligation. Residual linear DNA is enzymatically degraded with an exonuclease cocktail, leaving highly pure gDNA circles. Circularized gDNA is treated in vitro with ABE or CBE RNP complexes to nick the target DNA strand and deaminate adenine bases to inosine or cytosine bases to uracil (within the base-editing window) on the nontarget strand at on-target and off-target sites (red). For ABEs, nicked inosine-containing gDNA circles are then processed with endonuclease V, which cleaves DNA adjacent to inosines. For CBEs, uracil-containing DNA circles are treated with USER, which excises the uracil base to produce linear DNA with 5′ staggered ends. The 5′ overhangs are filled in with Klenow exo-, end-repaired, ligated to sequencing adaptors and amplified for selective high-throughput sequencing. b, Visualization of detected off-target sites identified by CHANGE-seq-BE aligned against the intended target site for ABE:gRNA (ABE8e-NRCH:HBBS-gRNA) complexes targeted against HBB. The intended target sequence is shown in the top line and off-target sites are ordered from top to bottom by CHANGE-seq-BE read count. Mismatches to the intended target sequence are indicated by colored nucleotides; matches are shown as dots and read counts and A-to-I (G) deamination frequencies (%) are shown at the end of each line (only the top off-target sites are listed). Representative alignment of CHANGE-seq-BE reads of the ABE8e-NRCH:HBBS-gRNA target, as visualized by the Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV) for an off-target site on chr2. The target adenine base is highlighted in red, the protospacer-adjacent motif (NRCH) is shown in bold and the single-stranded DNA breaks are marked with colored arrows by nCas9 (purple) and endonuclease V (red). c, Visualization plot of off-target sites aligned against the intended target site for selected eA3A-BE3:RNF2 complexes. The intended target sequence is shown in the top line and off-target sites are ordered by descending CHANGE-seq-BE read count. Mismatches to the intended target sequence are indicated by colored nucleotides and the arrow indicates the on-target site. Alignment of CHANGE-seq-BE reads of the eA3A-BE3-NGG:RNF2 gRNA off-target site on chr17, as visualized by the IGV. The target cytosine base in the editing window is highlighted in red, the protospacer-adjacent motif (NGG) is depicted in bold and single-stranded breaks made by USER (red) and nCas9 (purple) are indicated with respective colored arrows.

However, a major challenge we initially encountered was that the addition of the required end-repair step substantially decreased the enrichment of editor-modified DNA20. To gauge the performance of our initial CHANGE-seq for base editor approach, we quantified the number of validated off-target sites detected for an ABE8e RNP targeting the HBB gene (ABE8e-NRCH:HBBS-gRNA) that we previously characterized extensively and validated 54 off-target sites11. At first, we found that addition of an end-repair step to fill in 5′ overhangs and detect base-editor-modified gDNA resulted in high background and detection of only a small fraction (20%) of previously validated off-target sites (Extended Data Fig. 1a). We hypothesized that residual linear DNA molecules could become competent for adaptor ligation after end repair. After systematic optimization of the entire workflow, where we varied circularized gDNA exonuclease treatments, base-editing reaction conditions and end-repair protocols, we identified an optimized protocol (Supplementary Note 1 and Supplementary Protocol) that consistently detected all 54 previously validated ABE8e-NRCH:HBBS-gRNA off-target sites, which we called CHANGE-seq-BE (Extended Data Fig. 1a).

For ABEs, CHANGE-seq-BE reads capture a distinct molecular signature of base editing in vitro, evidence of A-to-I deamination as inosine bases are converted to guanine after PCR amplification, increasing confidence in sites nominated by our method. We observed a range of deamination frequencies of 25–48% in top ABE8e-NRCH:HBBS-gRNA off-target sites nominated by CHANGE-seq-BE (Fig. 1b).

CHANGE-seq-BE is also readily adaptable to CBEs, as long as high-quality, purified CBE proteins with efficient biochemical activity are available. To evaluate the activity of CBEs, we first performed in vitro cleavage profiling of a PCR amplicon using AnBE4max, A3A-BE3, eA3A-BE3, Td-CGBE and Td-CBEmax22,23,24 (Extended Data Fig. 1b) RNP complexes, followed by USER treatment to create DSBs. On the basis of protein activity, quality and purity, we selected eA3A-BE3 that showed 95% cleavage activity to further test with CHANGE-seq-BE. In contrast to ABEs, the USER enzyme recognizes and excises deaminated uracil bases from the noncomplementary strand and, thus, C-to-T base conversion is not detectable in CHANGE-seq-BE reads, although the breakpoint positions remain clear (Fig. 1c).

CHANGE-seq-BE identifies new bona fide off-target sites for ABE8e-NRCH:HBB

S target

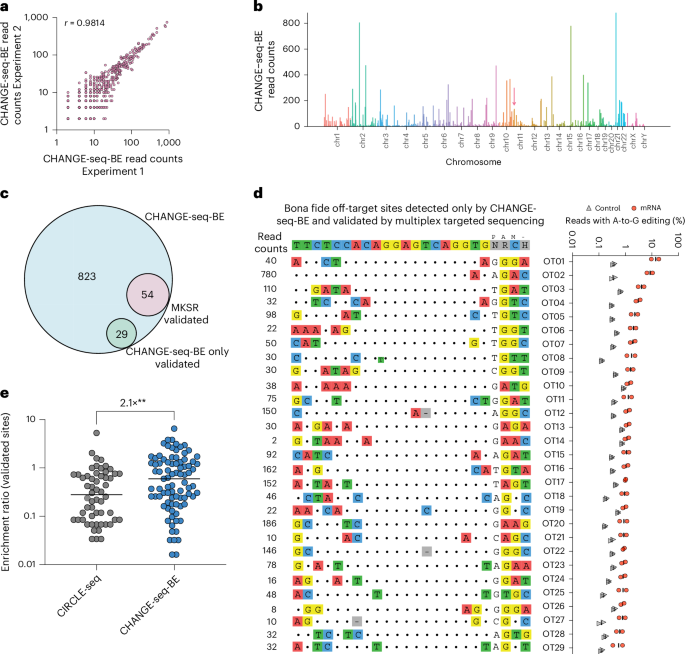

To initially evaluate technical reproducibility, we performed independent CHANGE-seq-BE library preparations and found that read counts from technical replicates were strongly correlated (Pearson’s correlation coefficient, r = 0.9814) (Fig. 2a), with sites of off-target activity distributed broadly throughout the genome (Fig. 2b and Supplementary Table 1). For this gRNA target, the on-target site did not have the highest CHANGE-seq-BE read counts, consistent with the lower specificity profile we observed.

a, Scatter plot showing read count correlation for two CHANGE-seq-BE library preparations of ABE8e-NRCH targeting HBBS. b, Manhattan plot showing the genome-wide distribution of CHANGE-seq-BE-detected sites for ABE8e-NRCH:HBBS-gRNA. The pink arrow indicates the on-target site. c, Venn diagram showing overlap between candidate off-target sites nominated by CHANGE-seq-BE for ABE8e-NRCH:HBBS-gRNA and nominated off-target sites for which off-target editing was observed by multiplex targeted sequencing in CD34+ cells (from a person with sickle cell disease) nucleofected with ABE8e-NRCH mRNA. d, Dot plot showing the percentage of sequencing reads containing A-to-G base editing within the protospacer positions 4–10 at off-target sites in gDNA samples derived from CD34+ HSPCs treated with ABE8e-NRCH mRNA (red, n = 2), or untreated controls (gray, n = 2). χ2 tests were performed between mRNA-treated and control samples. The FDR was calculated using the Benjamini–Hochberg method. Reported off-target sites were considered statistically significant with FDR ≤ 0.05 and difference ≥0.5% between treated and untreated controls. e, Dot plot showing the enrichment ratio for sites detected by CHANGE-seq-BE using ABE8e or for CIRCLE-seq using cognate Cas9 nuclease. Statistical analysis was conducted using an unpaired t-test (two-tailed) with P = 0.0098.

To determine whether CHANGE-seq-BE identifies base editor-specific off-target activity not detected by nuclease-specific methods, we compared the sites identified by CHANGE-seq-BE and CIRCLE-seq using ABE8e-NRCH base editor and Cas9-NRCH nuclease, respectively. We noted that CHANGE-seq-BE and CIRCLE-seq read counts were only weakly correlated (r = 0.34) (Extended Data Fig. 2a) and only 40% of the off-target sites detected by both methods overlapped (Extended Data Fig. 2b), suggesting that ABE8e genome-wide off-target activity quantitatively differs from Cas9 nuclease off-target activity. One explanation for some of these differences is the number and location of editable adenine bases within on-target and off-target sites, as off-target sites with mismatches of the editable adenine bases could eliminate base-editing activity without affecting nuclease activity.

To confirm that new off-target sites detected exclusively by CHANGE-seq-BE are bona fide off-target sites in cells, we performed multiplex targeted sequencing on 131 sites detected exclusively by CHANGE-seq-BE (Supplementary Table 2) using the same gDNA of CD34+ HSPCs treated with ABE8e-NRCH mRNA evaluated in our previous study11. We found that CHANGE-seq-BE identified all 54 known cellular off-target sites, as well as an additional 29 previously unknown bona fide off-target sites, 53% more than our initial screen with CIRCLE-seq (Fig. 2c), with ABE activity ranging from 0.55% to 13.9% (Fig. 2d). For the HBBS-gRNA bona fide off-target sites identified by CIRCLE-seq using Cas9 nuclease and CHANGE-seq-BE using ABE8e, we noted that the CHANGE-seq-BE enrichment ratio was significantly higher than that of CIRCLE-seq, by an average of 2.1-fold (Fig. 2e). HBBS-gRNA bona fide off-target activity occurred primarily in intergenic and intronic regions and six off-target sites were in exons (Extended Data Fig. 2c). Taken together, our results demonstrate the importance of using sensitive and unbiased base-editor-specific off-target discovery methods to comprehensively identify ABE genome-wide off-target activity.

CHANGE-seq-BE sensitively identifies bona fide off-target sites in human primary cells

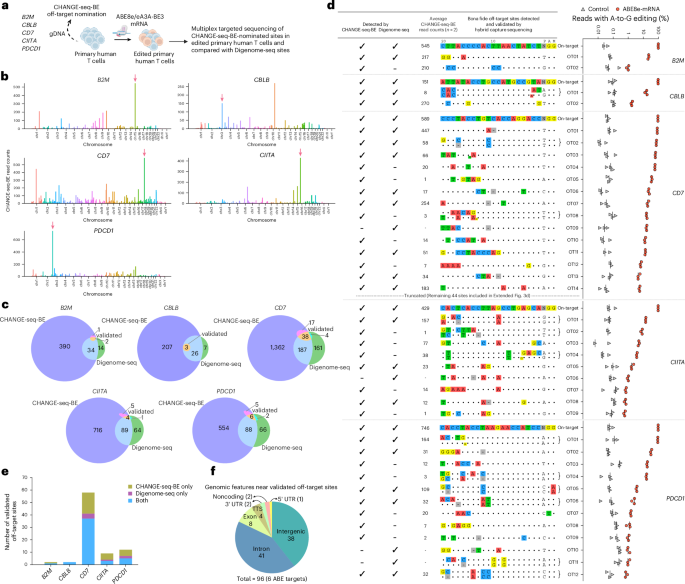

To systematically assess the genome-wide off-target activity of ABEs and CBEs in vitro, we performed CHANGE-seq-BE on five therapeutically relevant target sites in human primary T cells (B2M, CBLB, CD7, CIITA and PDCD1)25 and in human primary hepatocytes (PCSK9)26 with ABE8e (Fig. 3a and Extended Data Fig. 3a). Overall, CHANGE-seq-BE nominated a range of 236 to 1,604 on-target and off-target sites (total of 4,199) for B2M, CBLB, CD7, CIITA, PDCD1 and PCSK9 across the genome in two experimental replicates (Fig. 3b, Extended Data Fig. 3b and Supplementary Table 3).

a, Schematic of CHANGE-seq-BE off-target nomination at five targets in primary human T cells (B2M, CBLB, CD7, CIITA and PDCD1). b, Manhattan plot showing the genome-wide distribution of CHANGE-seq-BE-detected sites. The arrow (pink) indicates the on-target site. c, Venn diagrams depicting the overlap of off-target sites nominated by CHANGE-seq-BE and Digenome-seq and validated sites by hybrid capture sequencing. d, Bona fide cellular off-target sites detected by hybrid capture sequencing for the sites nominated by CHANGE-seq-BE and Digenome-seq, including CHANGE-seq-BE read counts (columns). Dot plot showing the percentage of sequencing reads containing A-to-G mutations within the protospacer positions 1–10 at off-target sites in gDNA samples from primary human T cells treated with ABE8e-NGG mRNA (red, n = 3) or untreated controls (gray, n = 3). χ2 tests were performed between mRNA-treated and control samples. The FDR was calculated using the Benjamini–Hochberg method. Reported off-target sites were considered statistically significant with FDR ≤ 0.05 and difference ≥0.5% between treated and untreated controls. e, Stacked bar plot representing the number of validated off-target sites exclusively identified by CHANGE-seq-BE (yellow), Digenome-seq (purple) or both (blue). f, Genomic features of validated off-target sites for six ABE targets (B2M, CBLB, CD7, CIITA, PDCD1 and PCSK9). TTS, transcription termination site; UTR, untranslated region. The proportion of transcribed regions in the validated sites was statistically significant compared to CHANGE-seq-BE-nominated sites using Fischer’s exact test (two-sided) with P = 0.0264. Panel a created with BioRender.com.

To compare the sensitivity of CHANGE-seq-BE to another leading off-target discovery method, we performed Digenome-seq on the same gRNA targets and evaluated them with matching analysis parameters. We identified a total of 796 on-target and off-target sites (ranging from 36 to 162 sites) for B2M, CBLB, CD7, CIITA and PDCD1. Next, we comprehensively evaluated 4,291 sites by hybrid capture sequencing for the sites nominated by either of the methods on gDNA obtained from edited cells compared to unedited controls. At these sites that were successfully captured and amplified, 96 sites showed significant off-target alterations (Supplementary Table 4), with cellular activity ranging from 0.44% to 93.1% (Fig. 3c,d and Extended Data Fig. 3c,d). At 83 (of 96) bona fide T cell off-target sites, 33.3–100% of sites were identified by both methods, 6.9–16.7% of sites were identified by Digenome-seq and 29.3–55.6% of sites were identified exclusively by CHANGE-seq-BE (Fig. 3e). Additional analysis of off-target sites with relaxed parameters found an additional six validated sites (Supplementary Note 2 and Supplementary Table 5).

To better understand the functional consequences of off-target activity for ABE targets, we annotated and analyzed the genomic locations of off-target sites by CHANGE-seq-BE and Digenome-seq. The proportion of nominated off-target sites found across various genomic regions (intronic, intergenic, transcribed and promoter) was similar between CHANGE-seq-BE and Digenome-seq (Extended Data Fig. 3e). Both nominated and validated off-target sites occurred predominantly in intergenic and intronic regions, consistent with their abundant representation within the human genome. Compared to the proportion of CHANGE-seq-BE-nominated off-target sites (10.3%), validated cellular off-target sites (17.7%) were significantly enriched in transcribed regions (Fig. 3f).

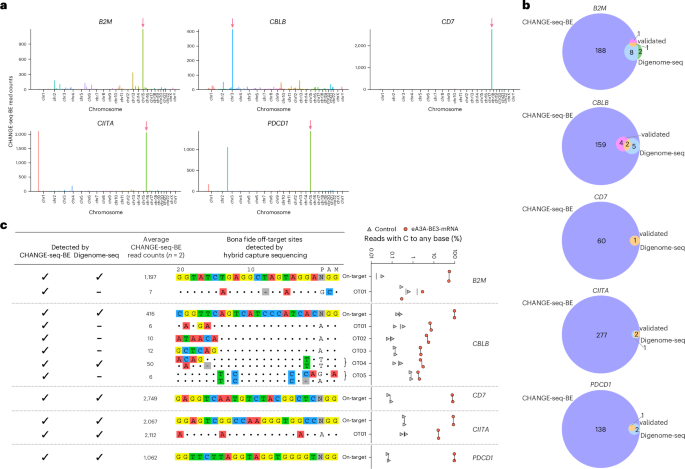

Similarly, we performed CHANGE-seq-BE and Digenome-seq using eA3A-BE3 to target B2M, CBLB, CD7, CIITA and PDCD1 regions at different loci. We identified a total of 850 on-target and off-target sites (ranging from 61 to 198) by CHANGE-seq-BE and 25 sites (ranging from 3 to 11) by Digenome-seq for B2M, CBLB, CD7, CIITA and PDCD1 targets, respectively (Fig. 4a,b and Supplementary Table 6). By hybrid capture sequencing, we evaluated 691 sites nominated by CHANGE-seq-BE and Digenome-seq for all five gRNA targets. Both methods identified on-target editing for all targets with cellular activity ranging from 52.3% to 97.6%. Both methods also detected a high-frequency off-target site (OT01) for CIITA that has a wobble mismatch to the intended target with 17% off-target editing. However, many low-frequency off-target sites with editing rates ranging from 1.7% to 7.5% were not identified by Digenome-seq and were only discovered by CHANGE-seq-BE (Fig. 4c and Supplementary Table 7).

a, Manhattan plot showing the genome-wide distribution of off-target sites detected by CHANGE-seq-BE for the targets B2M, CBLB, CD7, CIITA and PDCD1. The arrow (pink) indicates the on-target site. b, Venn diagram depicting the overlap of off-target sites detected by CHANGE-seq-BE, Digenome-seq and validated off-target sites. c, Bona fide cellular off-target sites by hybrid capture sequencing for the sites nominated by CHANGE-seq-BE and Digenome-seq, including CHANGE-seq-BE read counts (columns) with sequences. Dot plot showing the percentage of sequencing reads containing C-to-any mutations within the protospacer positions 1–10 at off-target sites in gDNA derived from primary human T cells treated with eA3A-BE3 mRNA (red) or untreated controls (gray) (n = 2). χ2 tests were performed between mRNA-treated and control samples. The FDR was calculated using the Benjamini–Hochberg method. Reported off-target sites were considered statistically significant with FDR ≤ 0.05 and difference ≥0.5% between treated and controls.

In sum, our data show that CHANGE-seq-BE is more sensitive than Digenome-seq while requiring 20-fold fewer sequencing reads. CHANGE-seq-BE is a strong predictor of base editor cellular off-target activity in human primary cells and can be used to select candidate target sites for both routine and therapeutic applications.

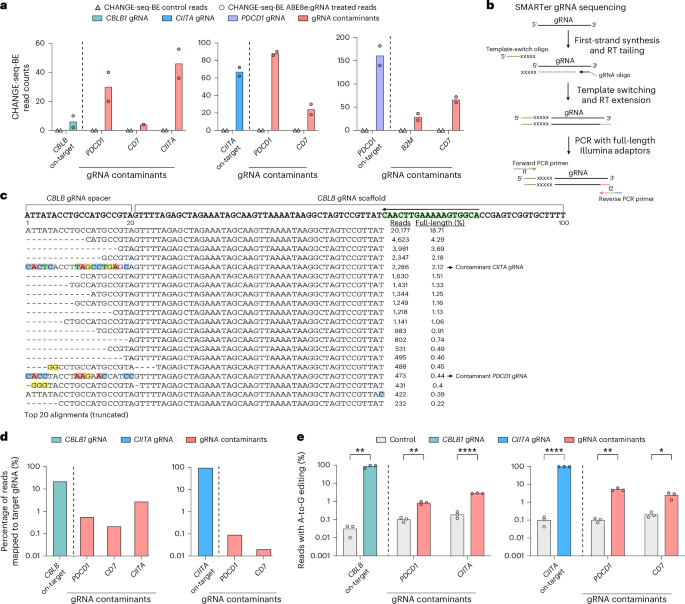

CHANGE-seq-BE identified unexpected synthetic gRNA contaminants

Safety risks specifically associated with human genome-editing products include unintended on-target and off-target activity and their long-term consequences. One less obvious but key concern is that contamination in a critical genome-editing component such as the gRNA could direct genome editing to unintended on-target sites. Chemically modified synthetic gRNAs are now a commonly used product in genome-editing experiments, particularly in primary cells, because of enhanced activity and stability27.

In initial pilots of CHANGE-seq-BE experiments using research-grade, chemically synthesized and high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC)-purified gRNAs, we observed CHANGE-seq-BE read counts across multiple targets in base-editor-treated samples but not in untreated controls, suggesting activity of contaminating synthetic gRNAs (Fig. 5a). We detected strong, unintended activity at PDCD1, CD7 and CIITA target sites in gDNA samples treated with the CBLB gRNA target site; similarly, PDCD1 and CD7 base editing mutation-containing reads were found in gDNA samples treated with CIITA gRNA and B2M and CD7 unintended on-target edited reads were found in gDNA samples treated with PDCD1 gRNA. In hindsight, according to manufacturer discussions, the most likely source of this cross-contamination during manufacturing was the sequential purification of these gRNAs over the same HPLC column. Detectable cross-contaminating activity was mitigated by a more stringent, column clearing-in-place procedure used in a second batch of gRNAs from the same manufacturer.

a, Bar plot showing CHANGE-seq-BE read counts for three synthetic chemically modified gRNAs (CBLB, CIITA and PDCD1) from the manufacturer supplier A (batch 1) and the unexpected detection of gRNA contaminants (red). Data are shown as the mean (n = 2). b, SMARTer gRNA-sequencing workflow. c, Alignment plot for CBLB gRNA target displaying top 20 mapped reads. Mismatched nucleotides in the target sequence are highlighted in colors (blue, green, red and yellow) representing potential contaminants CIITA and PDCD1. The arrow highlighted in the scaffold region (green) shows the scaffold specific primer used for first cDNA synthesis. d, Bar plot showing the percentage of sequencing reads mapping to target gRNAs, for one specific synthetic gRNA supplier A (batch 1). The activity of gRNA contaminants is shown in red. e, Bar plot showing the percentage of sequencing reads containing A-to-G mutations within the protospacer positions 4–10 at off-target sites in gDNA samples from primary human T cells treated with ABE8e in the mRNA format and gRNAs targeting CBLB or CIITA, as well as the detection of contaminant gRNAs (red) during the manufacture process. Data are shown as the mean. Unpaired t-tests (two-sided) were performed using the Holm–Šídák multiple-comparisons method (n = 3); adjusted P = 0.0013 (CBLB on-target), 0.0013 (PDCD1), 0.00002 (CIITA), <0.000001 (CIITA on-target), 0.0014 (PDCD1) and 0.0187 (CD7).

To identify and measure the frequency of contaminating gRNAs, we used a gRNA-sequencing assay28 based on an established small RNA-sequencing technology (Fig. 5b). We then evaluated five research-grade gRNA sequences from three synthetic gRNA manufacturer suppliers (A, B and C) for the presence of gRNA contaminants (Extended Data Fig. 4a). We detected the presence of contaminating gRNAs in CBLB and CIITA gRNAs from supplier A (batch 1), with frequency ranging from 0.09% to 2.71% (Fig. 5c,d).

To determine whether the relatively minute amounts of gRNA contaminants detected in vitro by CHANGE-seq-BE activity and gRNA sequencing would be active in cells, we performed targeted sequencing of gDNA from primary human T cells edited with ABE8e, with gRNAs manufactured by supplier A targeting CBLB and CIITA loci. For cells with intended CBLB edits, we additionally evaluated editing at PDCD1 and CIITA on-target sites and, for cells with intended CIITA editing, we also evaluated PDCD1 and CD7 on-target sites by targeted sequencing. We detected point mutations consistent with adenine base editing in all unintended on-target sites associated with contaminating gRNAs evaluated, with activity ranging from 0.83% to 5.24% (Fig. 5e).

Our results highlight one additional feature of using sensitive and unbiased genome-wide methods for base editor off-target discovery is identification of unintended ‘on-target’ activity of contaminant gRNAs. This may be a pervasive issue when multiple chemically synthesized gRNAs are purified using the same chromatography supplies and caution is warranted to minimize gRNA synthesis contamination risk, particularly for therapeutic applications.

CHANGE-seq-BE reveals biological activity differences between nucleases and base editors

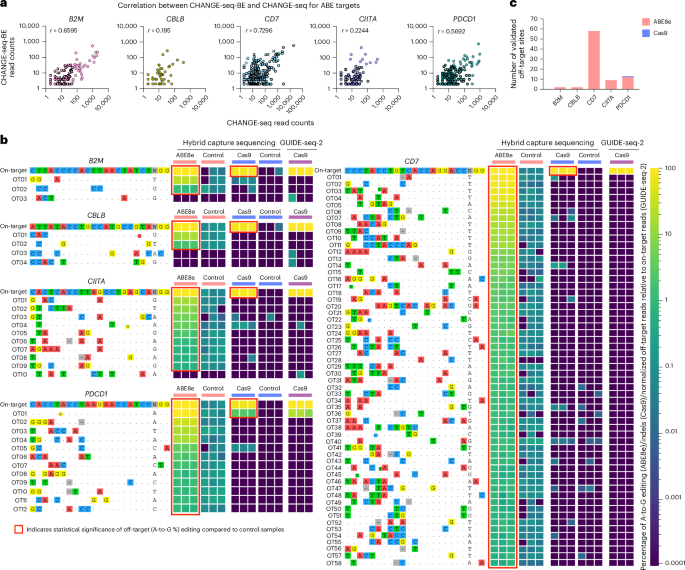

To evaluate biochemical activity differences between base editors (ABE8e) and nucleases (Cas9), we additionally performed CHANGE-seq (with Cas9 nuclease) on gDNA from human primary T cells for the same five gRNAs (B2M, CBLB, CD7, CIITA and PDCD1) we previously evaluated with ABEs. A total of 7,430 on-target and off-target sites were detected by CHANGE-seq for all five targets (in contrast to 3,734 sites by CHANGE-seq-BE; Supplementary Table 3). Read counts from experimental replicates were strongly correlated for CHANGE-seq (r > 0.86) and CHANGE-seq-BE (r > 0.96) (Extended Data Fig. 5a,b). However, across methods, CHANGE-seq and CHANGE-seq-BE read counts were less correlated and varied depending on the gRNA target (r = 0.2–0.73) (Fig. 6a). Our results show that the biochemical activities of ABE8e base editor and Cas9 are both highly reproducible and distinct.

a, Scatter plot showing read counts correlation between CHANGE-seq-BE and CHANGE-seq for five ABE targets (B2M, CBLB, CD7, CIITA and PDCD1). b, Sequences of bona fide validated off-target sites for five gRNA targets in hybrid capture sequencing. The heat map represents the percentage of A-to-G editing by ABE8e base editor or indels by Cas9 nuclease (hybrid capture sequencing) or normalized off-target reads relative to on-target reads (GUIDE-seq-2). Cas9-mediated cellular off-target sites are highlighted in red box. χ2 tests were performed between mRNA-treated and control samples. The FDR was calculated using the Benjamini–Hochberg method. Reported off-target sites were considered statistically significant with FDR ≤ 0.05 and difference ≥0.5% between treated (red box) and controls. c, Stacked bar plot representing the total of number of validated off-target sites for ABE8e and Cas9 mRNA edited T cells.

To directly assess the cellular off-target activity differences between Cas9 nuclease and ABEs, we edited T cells for all five targets with Cas9 mRNA and performed hybrid capture targeted sequencing on a total of 2,226 off-target sites (including 1,436 off-target sites nominated only by Cas9 CHANGE-seq). High-frequency on-target editing was achieved for both ABE8e (96.5–99.4% A-to-G base editing; Fig. 3d) and Cas9 (70.7–92% indels) for all five targets. A total of 83 bona fide T cell off-target sites with base editing frequencies ranging from 0.44% to 93.1% were identified for ABE8e across all five targets. In contrast, only one bona fide off-target site with an average of 2.4% indels was confirmed for Cas9 targeting PDCD1 (Fig. 6b,c).

To independently confirm the editing activity measured by hybrid capture sequencing, we performed GUIDE-seq-2 (ref. 29) with Cas9 delivered as a mRNA for all five targets (Extended Data Fig. 6a). Under matching delivery conditions, we observed GUIDE-seq-2 off-target activity profiles that were consistent with our hybrid capture targeted sequencing results (Fig. 6b), where only OT01 for PDCD1 was clearly above the lower limits of detection of GUIDE-seq-2 (Extended Data Fig. 6b). GUIDE-seq-2 with Cas9 RNP resulted in slightly more but still fairly low off-target activity, ranging from 0.01% to 3.4%.

Overall, base editors have different off-target editing profiles when directly compared to cognate nucleases. For example, our comparisons of Cas9 and ABE8e under controlled delivery conditions demonstrate that ABE8e has significantly increased off-target activity compared to Cas9, with 98.8% of validated off-target sites unique to ABE8e. Therefore, it is essential to use direct methods to evaluate the off-target activity of base editors rather than relying on nuclease-based methods only.

CHANGE-seq-BE supports emergency IND for personalized genome-editing treatment

We applied the sensitive off-target detection capability of CHANGE-seq-BE to quantitatively characterize the genome-wide gRNA-dependent off-target profile of an ABE base-editing strategy to treat a person with X-HIGM syndrome by correcting the CD40L mutation (c.658C>T; p.Q220X). Using CHANGE-seq-BE, we identified a total of 81 potential off-target sites across the human genome and experiments were well correlated across two technical replicates (Extended Data Fig. 7a,b). Most of these off-target sites occurred in intronic and intergenic regions and in two exonic regions (Extended Data Fig. 7c). With confirmatory testing by multiplex targeted sequencing using rhAmpSeq, we observed on-target editing of 95.4% with no detectable off-target effects above the limit of threshold compared to controls (Extended Data Fig. 7d). This successfully supported an emergency personalized base editor hematopoietic stem cell and T cell treatment of a person with CD40L HIGM syndrome (NCT06959771), attesting to the IND-enabling role of CHANGE-seq-BE.