Predicting small molecule–RNA interactions without RNA tertiary structures – Nature Biotechnology

SMRTnet dataset collection and processing

To train SMRTnet, we first filtered 2,477 structures (1.27%) from 195,340 structures in the PDB (as of January 2024) that contained at least one RNA and one small molecule using atomium89. We then removed nontherapeutically relevant small molecules and structures with fewer than 31 RNA residues, as well as binding sites where more than 50% of the residues within 10 Å were proteins. This filtering process yielded 1,061 high-quality SRI structures. Next, we converted the RNA tertiary structures from these 1,061 SRIs into secondary structures using DSSR90 and identified the binding positions of RNA residues within 10 Å of the small molecule using atomium23,89. These binding positions were subsequently extended by 15 nt in both the 5′ and the 3′ directions to generate 31-nt RNA fragments. Finally, we converted the chemical structures of small molecules to canonical SMILES using the RDKit91 and each SMILES was paired with its corresponding RNA fragment to form a positive sample. Additionally, we generated negative samples by randomly pairing RNA fragments with small molecules after removing known interaction pairs and maintained specific positive-to-negative sample ratios (1:1, 1:2, 1:3, 1:4, 1:5 and 1:10) using different random seeds (1, 2, 3, 4 and 42). This process resulted in the SMRTnet dataset. The SMRTnet dataset was divided into training (80%), validation (10%) and test (10%) sets using a ligand-based data-splitting strategy, ensuring that no SMILES in the test set appeared in the training or validation sets. We also used fivefold CV to evaluate model stability and ensured that no SMILES were shared between the validation or test sets across different folds. Details of the SMRTnet dataset are provided in Supplementary Table 1.

To evaluate potential data leakage in SMRTnet, we constructed several revised versions of the test set of SMRTnet. On the ligand side, we tested a range of maximum similarity threshold from 0.7 to 1.0, with intervals of 0.1 (with 1.0 corresponding to our ligand-based data-splitting strategy). For each threshold, we excluded small molecules (along with their corresponding RNAs) from the test set of SMRTnet if their Tanimoto similarity with any training set small molecules exceeded the specified threshold. On the RNA side, we generated a multistrand-binding-site exclusion test set of SMRTnet by removing RNAs (along with their corresponding small molecules) that shared identical multistrand binding sites with any RNA in the training set across fivefold CV.

To investigate potential biases of quantitative structure–activity relationship in SMRTnet, we constructed a modified test set of SMRTnet, termed the RNA′ test set of SMRTnet. Specifically, during each round of fivefold CV, each ligand in the positive samples in the test set was replaced with a different ligand randomly sampled from the test set, while keeping the corresponding all fragments within an RNA pocket and label unchanged. In a further variant, instead of preserving the positive label of the permuted samples, we modified them as negative and combined it with the original test set of SMRTnet, termed the RNA″ test set of SMRTnet.

SMRTnet-benchmark dataset collection and processing

To evaluate SMRTnet, we constructed a benchmark dataset comprising 2,011 experimentally validated SRIs and noninteraction pairs, including 1,665 interaction pairs and 346 noninteraction pairs. This dataset, referred to as the SMRTnet-benchmark dataset, excludes any small molecule–RNA pairs present in the SMRTnet dataset (deduplicated with 100% identity). Specifically, we obtained the RNA sequences and their secondary structure from the corresponding publications, manually drew the chemical structures of the small molecules on the basis of these publications and converted them into canonical SMILES using the Open Babel92 web server. In total, we collected 1,795 interaction and noninteraction pairs from 178 papers across four published databases: R-BIND45,46, R-SIM47, SMMRNA48 and NALDB49. Additionally, we collected 216 interaction and noninteraction pairs not included in any of these databases from 22 new publications9,60,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112, which we refer to as the ‘NewPub’ subset. Details of the SMRTnet-benchmark dataset are provided in Supplementary Table 2.

Drug-screening dataset collection and processing

To evaluate SMRTnet’s capability in drug discovery, we constructed datasets for identifying SRIs, referred to as the drug-screening datasets. These datasets comprised ten disease-associated RNA structural elements and a curated library containing 7,350 compounds of natural products and metabolites. Specifically, the RNA structural elements included MYC IRES60, pre-miR-155 (ref. 60), HOTAIR helix 7 (ref. 65), CAG repeat expansion in HTT gene113, HIV RRE IIb (ref. 114) and five elements in SARS-CoV-2 5′ UTR regions68 (including SL1, SL2/3, SL4, SL5a and SL5b). We truncated each full-length RNA to 31 nt and predicted its secondary structure from sequence using RNAstructure54, ensuring that the predicted secondary structures were consistent with experimentally validated RNA secondary structures reported in previous studies. Additionally, we collected several natural product libraries from the in-house chemical library of the Center of Pharmaceutical Technology, Tsinghua University (http://cpt.tsinghua.edu.cn/hts/), including the natural product library for high-throughput screening (n = 4,160), the BBP natural product library (n = 3,200), the TargetMol natural compound library (n = 409), the MCE natural product library (n = 1,384) and the Pharmacodia natural product library (n = 935). From these collections, we constructed a natural product library comprising 7,350 unique compounds with distinct CAS numbers and obtained their canonical SMILES using RDKit91. The compounds used in the experiments were purchased from Topscience. Details of the drug-screening datasets are provided in Supplementary Tables 3 and 4.

We applied a stratified sampling approach to generate a downsampled subset of compounds for experimental validation of MYC IRES binding on the basis of the full natural product library. Specifically, we performed binding predictions for MYC IRES using SMRTnet against the full natural product library (n = 7,350) and then divided the predicted binding scores into ten intervals with increments of 0.1. From each interval, we randomly selected 5% of the compounds, except for the 0.9–1.0 interval, from which 100% of compounds (n = 7) were included because of the limited number in this interval. This stratified sampling approach resulted in a downsampled screening library of 376 compounds for experimental validation. Details of the a downsampled drug-screening library are provided in Supplementary Table 5.

MYC IRES mutation dataset construction

To evaluate model interpretability and identify the small-molecule-binding sites on MYC IRES, we constructed an MYC IRES mutation dataset comprising 20 mutant RNAs. Specifically, we generated five distinct types of RNA-binding sites by altering the nucleotides within the predicted small-molecule-binding region, each type consisting of four RNA variants. The original 2 × 2 internal loop of MYC IRES was altered to form two types of 1 × 1 internal loops, 3 × 3 internal loops and fully complementary base-paired structures. We also preserved the original 2 × 2 internal loop by modifying only its sequence. All 20 mutant RNAs were folded to satisfy minimum free energy criteria, ensuring that they adopted the expected conformations consistent with in vitro experiments. Details of the MYC IRES mutation dataset are provided in Supplementary Table 6.

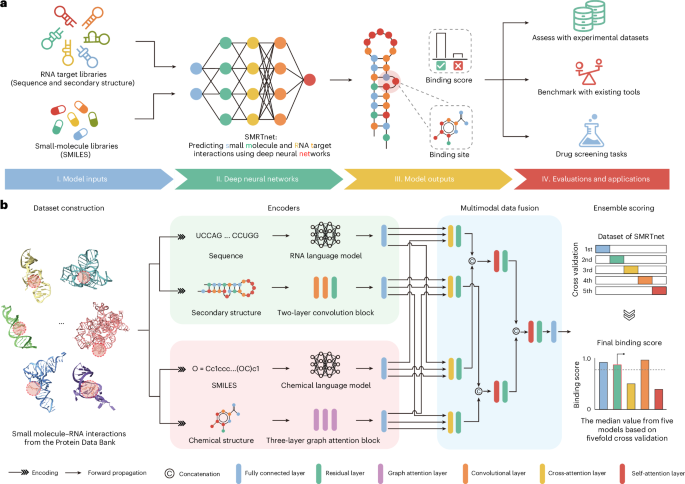

Architecture of SMRTnet

SMRTnet is a binary classification model with three inputs (RNA sequence, RNA secondary structure and small-molecule SMILES) and one output (binding score). Specifically, each RNA sequence is a 31-nt sequence composed of {A, U, C, G}. The RNA secondary structure in each sample is represented by 31-nt dot-bracket notations using {‘(‘, ‘.’, ‘)’}. The small molecule is encoded using canonical SMILES, processed by RDKit91. Labels in each sample are binary with two symbols (‘1’ for positive samples and ‘0’ for negative samples). During inference, SMRTnet processes input RNAs (≥31 nt, regardless of the presence of a known binding site) with a sliding-window approach. The binding score is computed as follows:

$$\,\,\begin{array}{l}\mathrm{SMRTnet}(x,y,z)\\ =\sigma ({f}_{\mathrm{FC}}({f}_{\mathrm{MDF}}({f}_{\mathrm{CNN}-\mathrm{Res}}(x,y){,f}_{\mathrm{RNASwan}-\mathrm{seq}}(x),{f}_{\mathrm{GAT}}({z}^{{{{\prime} }}}){,f}_{\mathrm{MoLFormer}}(z))))\end{array}$$

(1.1)

[where x is the RNA sequence, y is the RNA secondary structure with dot-bracket notation, z is the canonical SMILES of small molecule and z′ is the two-dimensional (2D) molecular graph of the small molecule derived from z using RDKit91. σ is the sigmoid activation function, \({f}_{\mathrm{FC}}\) is a fully connected layer, \({f}_{\mathrm{MDF}}\) is the MDF module, \({f}_{\mathrm{CNN}-\mathrm{Res}}\) is the RNA structure encoder based on CNN with ResNet, \({f}_{\mathrm{RNASwan}-\mathrm{seq}}\) is the RNA sequence encoder based on RNA language model, \({f}_{\mathrm{MoLFormer}}\) is the drug sequence encoder based on chemical language model and \({f}_{\mathrm{GAT}}\) is the small-molecule structure encoder based on GAT115. The model output is transformed from the output value of the \({f}_{\mathrm{FC}}\) through the σ activation layer.

RNA sequence encoder

We developed an RNA language model, RNASwan-seq, for learning RNA sequence representations (Extended Data Fig. 1a). The pretraining dataset for RNASwan-seq was compiled from seven sources: the European Nucleotide Archive116, National Center for Biotechnology Information nucleotide database117, GenBank118, Ensembl119, RNAcentral120, CSCD2 (ref. 121) and GreeNC 2.0 (ref. 122), encompassing a total of 470 million RNA sequences. Redundant sequences with 100% sequence identity were removed using MMSeqs2 (ref. 123), resulting in approximately 214 million unique RNA sequences. A random splitting strategy with a 30% sequence identity threshold was applied to divide the data into training and test sets for self-supervised training.

RNASwan-seq consisted of 30 transformer encoder blocks with rotary positional embeddings (RoPEs). Each block includes a feedforward layer with a hidden size of 640 and 20 attention heads. During training, a random cropping strategy was applied to extract 1,024-nt segments from the full-length RNA sequences in each iteration and 15% of nucleotide tokens were randomly selected for potential replacement. The model was trained using masked language modeling (MLM) to recover the original masked tokens using cross-entropy loss. A flash attention mechanism was used to accelerate the training process. The training process is formulated as an objective function as follows:

$${{\mathcal{L}}}_{\mathrm{MLM}}={{\mathbb{E}}}_{x\sim X}{{\mathbb{E}}}_{{x}_{{\mathcal{M}}}\sim x}\mathop{\sum }\limits_{i\in {\mathcal{M}}}-\log p({x}_{i}|{x}_{/{\mathcal{M}}})$$

(2.1)

where \({\mathcal{M}}\) represents indices of masked tokens randomly sampled from each input sequence x. For each masked token, given masked sequence \({x}_{/{\mathcal{M}}}\) as context, the objective function minimizes the negative log likelihood of the true nucleotides \({x}_{i}\). Finally, the pretrained model was integrated into SMRTnet as an RNA sequence encoder using a fine-tuning strategy.

RNA structure encoder

We designed an RNA structure encoder (Extended Data Fig. 1b), adapted from our previous work31. This encoder represents the RNA sequence x (four-dimensional) using one-hot encoding and incorporates RNA secondary structure y (one-dimensional, 1D), expressed in dot-bracket notation, to form a five-dimensiaonal vector \(x{\prime}\). The embedding of the RNA structure encoder is computed as follows:

$${f}_{\mathrm{CNN}-\mathrm{Res}}\left(x,y\right)={f}_{{\rm{R}}}\left({f}_{\mathrm{SE}}\left({f}_{{\rm{C}}}(x{\prime} )\right)\right)$$

(3.1)

Here, \({f}_{{\rm{C}}}\) denotes the convolutional block, \({f}_{\mathrm{SE}}\) denotes the squeeze–excitation (SE) block and \({f}_{{\rm{R}}}\) denotes the residual block. These three blocks are defined as follows:

$${f}_{{\rm{C}}}(x{\prime} )=\mathrm{ReLU}\left(\mathrm{BN}\left(\mathrm{Conv}\left(x{\prime} \right)\right)\right)$$

(3.2)

In \({f}_{C}\), \(\mathrm{ReLU}\) represents the rectifier linear unit activation function, \(\mathrm{BN}\) represents the batch normalization layer and \(\mathrm{Conv}\) represents the 2D convolutional layers. This configuration ensures that the output shape of the convolution layers matches that of the input shape.

$${f}_{\mathrm{SE}}\left(x{\prime} \right)=x{\prime} \bigotimes {\sigma (f}_{\mathrm{ex}}({f}_{\mathrm{sq}}\left({x}^{{\prime} }\right)))$$

(3.3)

In \({f}_{\mathrm{SE}}\), the SE block functions as a channel-wise self-attention mechanism that identifies binding-site patterns through weight recalibration. \(\bigotimes\) represents channel-wise multiplication between the input and the learned vector by SE block. The SE block first compresses the global sequence context using the global average pooling function \({f}_{\mathrm{sq}}\) and then transformed it into a set of channel-wise weights, scaled between 0 and 1, through a nonlinear transformation \({f}_{\mathrm{ex}}\), which consists of two fully connection layers and a ReLU activation function.

$${f}_{{\rm{R}}}\left(x\right)={f}_{{\rm{R}}1}(\mathrm{AvgPool}({f}_{{\rm{R}}2}(x)))$$

(3.4)

In \({f}_{{\rm{R}}}\), \({f}_{{\rm{R}}1}\) denotes residual blocks with 1D convolutional kernels, learning combined sequence and structural patterns, while \({f}_{{\rm{R}}2}\) denotes residual blocks with 2D convolutional kernels, capturing spatial context features that localize the precise binding site. The \(\mathrm{AvgPool}\) function is an average pooling layer that convert the 2D feature maps into the 1D vectors.

Small-molecule SMILES encoder

We introduced MoLFormer28, a chemical language model, as the small-molecule sequence encoder to represent the small molecules. The model uses a linear attention mechanism with RoPE to process SMILES derived from approximately 1.1 billion unlabeled molecules in the PubChem124 and ZINC125 databases. Specifically, MoLFormer is a transformer-based encoder with linear attention, comprising 12 layers, 12 attention heads per layer and a hidden state size of 768. As a result, each SMILES is encoded into an \(L\times 768\) matrix. Finally, we fine-tuned the final checkpoint of MoLFormer (N-Step-Checkpoint_3_30000.ckpt) to integrate it into SMRTnet.

Small-molecule structure encoder

We designed a three-layer GAT block as the small-molecule structure encoder, which adaptively learns edge weights and captures node representations through message passing for small molecule (Extended Data Fig. 1c). Specifically, each canonical SMILES is converted into a 2D molecular graph \(G=(V,E)\) using RDKit, where V represents the set of atomic nodes for molecule and \(E\) represents the set of edges connecting these nodes. Each node is represented by a 74-dimensional feature vector based on the DGL-LifeSci package126. For molecules with fewer nodes, virtual nodes (zero-padded) are added to ensure dimensional consistency. The embedding of a small-molecule structure encoder is computed as follows:

$${v}_{i}^{l+1}=\phi \left({v}_{i}^{l},{\oplus }_{j\in {{\mathscr{N}}}_{i}}\psi \left({v}_{i}^{l},{v}_{j}^{l}\right)\right)$$

(4.1)

Here, \(\phi\) and \(\psi\) represent the learnable aggregation and attention functions, respectively. \({{\mathscr{N}}}_{i}\) represents the set of neighbors of atom i, l indexes the graph attention layer and \(v\) represents the feature vector of each node. Masked attention is applied to restrict computation to neighboring nodes, as defined by the adjacency matrix. Attention weights are normalized across all potential neighbors using the SoftMax function to ensure comparability. The final molecular representation is derived by iteratively aggregating the bond-connected atom features along with their associated chemical bond features.

MDF module

We proposed a MDF module consisting of three layers, including one coattention layer and two self-attention layers with different parameters (Extended Data Fig. 1d). Each layer incorporates residual blocks and layer normalization blocks, with concatenation blocks integrating multimodal features for the input to the next layer. This MDF module is defined as follows:

$$\,\,\begin{array}{l}{f}_{\mathrm{fusion}}({E}_{r},{E}_{s},{E}_{m},{E}_{t})\\ ={f}_{f3}\left({f}_{f2}\left({f}_{f1}\left({E}_{s},{E}_{r},{E}_{r}\right),{f}_{f1}\left({E}_{r},{E}_{s},{E}_{s}\right)\right),{f}_{f2}\left({(f}_{f1}\left({E}_{t},{E}_{m},{E}_{m}\right),{f}_{f1}\left({E}_{m},{E}_{t},{E}_{t}\right)\right)\right)\end{array}$$

(5.1)

Here, \({E}_{r}\) is the output of RNA sequence encoder, \({E}_{s}\) is the output of RNA structure encoder, \({E}_{m}\) is the output of small-molecule SMILES encoder and \({E}_{t}\) is the output of the small-molecule structure encoder. The first fusion layer \({f}_{f1}\) contains a co-attention block, while the second (\({f}_{f2}\)) and third (\({f}_{f3}\)) fusion layers contain self-attention block. The three fusion layers are constructed as follows:

For the first fusion layer \({f}_{f1}\), we implemented a co-attention mechanism based on ViLBERT29, which extends the BERT architecture to a multimodal, two-stream model.

$$\begin{array}{l}{f}_{f1}\left(Q,K,V\right)=Q+\text{cross}-\text{attention}\left(Q,K,V\right)=Q+\mathrm{Softmax}\left(\frac{{{QK}}^{T}}{\sqrt{d/h}}\right)\times V\\ Q={f}_{\mathrm{ln}}{(f}_{\mathrm{MLP}}({E}_{i})){;K}=V={f}_{\mathrm{ln}}{(f}_{\mathrm{MLP}}({E}_{\mathrm{corresponding}\,\mathrm{to}\,i})),i\in \left\{r,s,m,t\right\}\end{array}$$

(5.2)

For the second fusion layer \({f}_{f2}\) and third fusion layer \({f}_{f3}\), a self-attention mechanism is used to further enhance the integration of the sequence and structure features of small molecule and RNA, resulting in a single embedding to predict the binding score.

$$\begin{array}{l}{f}_{f2}\left(Q,K,V\right)={f}_{f3}\left(Q,K,V\right)=Q+\text{self}-\text{attention}\left(Q,K,V\right)\\ =Q+\mathrm{Softmax}\left(\frac{{\mathrm{QK}}^{{\rm{T}}}}{\sqrt{{\rm{d}}/{\rm{h}}}}\right)\times V\,Q=K=V\\ =[{f}_{\mathrm{ln}}\left(\mathrm{output\_}1\right),{(f}_{\mathrm{ln}}\left(\mathrm{output\_}2\right))\end{array}$$

(5.3)

Here, \({f}_{\mathrm{ln}}\) is the layer normalization block, \({f}_{\mathrm{MLP}}\) is the multilayer perceptron and \([]\) is the concatenation block. The output embedding dimension c is set to 128 across all three fusion layers. The number of attention heads \(h\) is set to 2 in \({f}_{f1}\) and \({f}_{f2}\) and to 8 in \({f}_{f3}\).

Training strategy of SMRTnet

SMRTnet uses supervised learning to predict binding scores between small molecules and RNA by minimizing the error between predicted binding scores and ground-truth labels. Specifically, SMRTnet optimizes its parameters by minimizing a loss function composed of binary cross-entropy loss and L2 regularization, calculated between the target labels T and predictions y across the training set.

$$\mathrm{Loss}(T,Y)=-\frac{1}{N}\mathop{\sum }\limits_{i=1}^{N}\left[{t}_{i}* \log {y}_{i}+\left(1-{t}_{i}\right)* \log \left(1-{y}_{i}\right)\right]+\lambda {\left|{\mathbb{W}}\right|}_{2}$$

(6.1)

Here, \({t}_{i}\) is the ground-truth label, \({y}_{i}\) is the predicted binding score, \({\mathbb{W}}\) represents all parameters of SMRTnet and \(N\) is the batch size. Model parameters were optimized using the Adam optimizer, an extension of stochastic gradient descent algorithm that adaptively adjusts step sizes and requires minimal hyperparameter tuning. Additionally, a warmup scheme with a linear scaling rule was applied to adjust learning rates during training.

To mitigate overfitting, each convolutional layer was followed by a batch normalization layer, each residual block was followed by a dropout layer and the L2 normalization on all parameters acted as a weight decay term to further reduce overfitting. Early stopping was used to halt SMRTnet training automatically when the validation auROC value did not improve for 20 consecutive epochs.

Ensemble scoring strategy of SMRTnet

We implemented an ensemble scoring strategy to enhance model robustness. Specifically, this strategy is defined as the median value of five models obtained from fivefold CV and a sliding-window approach was applied to process the input RNAs longer than 31 nt (refs. 31,41). The final binding score was calculated as follows:

$$F\left(r,s,L\right)=\left\{\begin{array}{cc}\mathop{\max }\limits_{i\in S}{f}_{\mathrm{median}}\left({r}_{i},{s}_{i}\right), & \,\,\,\,\,\,\,31\le L\le 40\\ \phi \left({f}_{\mathrm{median}}\left({r}_{i},{s}_{i}\right)\right), & L > 40\end{array}\right.$$

(7.1)

Here, F represents the ensemble scoring strategy, \({f}_{\mathrm{median}}\left({r}_{i},{s}_{i}\right)\) represents the median value of five models obtained from fivefold CV. Given an input RNA r and small molecule s, a sliding-window approach (window size = 31 nt, step size = 1 nt) is used to compute the binding scores for each RNA segment \({r}_{i}\) and its corresponding small molecule \({s}_{i}\). For input RNAs with lengths between 31 nt and 40 nt (\(31 < L\le 40\)), the final binding score is defined as the maximum binding score across all windows. For input RNAs longer than 40 nt (\(L > 40\)), \(\phi (\bullet )\) is applied to identify potential binding regions, which are characterized by at least four consecutive windows with binding scores greater than 0.5. The final binding score is then taken as the maximum score within the identified potential binding regions. If no such potential binding regions exist, the minimum binding score across all windows is taken as the final binding score and the small molecule–RNA pair is classified as unbound (Extended Data Fig. 2c).

Hyperparameters of SMRTnet

The hyperparameters of SMRTnet were determined through grid search. Specifically, we extensively evaluated and empirically tuned the hyperparameters of each module to achieve optimal model performance. The final hyperparameter settings of SMRTnet are described below.

Batch size

A batch size of 32 was used for all experiments.

Learning rate

Base learning rates of 1 × 10−4 and 1 × 10−5 were applied to SMRTnet and to RNASwan-seq and MoLFormer, respectively. A warmup strategy was used to scale the learning rate by a factor of 8 during initial training epochs.

Training epochs

Models were trained for up to 100 epochs, with early stopping triggered if no improvement in auROC value was observed on the validation set over 20 consecutive epochs.

Optimizer

The Adam optimizer was applied.

L

2 norm penalty

The L2 penalty weight (λ) was set to 1 × 10−6.

Loss function

Binary cross-entropy loss was used. Positive sample weights of 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 and 10 were applied on the basis of different positive-to-negative sample ratios.

Gradient clipping

Gradients were clipped using a maximum norm of 5.0.

Hyperparameters in RNA structure encoder

The optimal kernel size and padding were determined to be 7 and 3, respectively, on the basis of a grid search over (kernel size, padding) pairs: (3,1), (5,2), (7,3), (9,4) and (11,5). The optimal number of channel size was found to be 16, selected from the set {2, 4, 6, 8, 16, 32, 64}. Dropout rates of 0.5 and 0.3 were applied after each residual block.

Hyperparameters in small-molecule structure encoder

The optimal attention heads were set to 3, selected from the set {1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6}. The optimal number of GAT layers was set to 3, selected from the set {1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6}. The optimal output head dimension was set to 256, selected from the set {32, 64, 128, 256, 512}.

Hyperparameters in MDF module

We tested various configurations of the MDF module and fully connected decoder and identified the optimal combination of parameters. The first coattention layer used two attention heads with a dropout rate of 0.1; the second self-attention layer used two attention heads with a dropout rate of 0.1; the third self-attention layer used eight attention heads with a dropout rate of 0.3. The fully connected decoder consisted of four layers with 1,024, 1,024, 1,024 and 512 nodes, respectively.

Evaluation of SMRTnet

We used accuracy, recall, precision, F0.5 score, auROC and auPRC (area under the precision–recall curve) to assess model performance. These metrics were calculated using the Python package scikit-learn (https://scikit-learn.org/stable/). Specifically, accuracy was calculated using the accuracy_score function from sklearn.metrics, which measures the proportion of correct predictions among all predictions. Precision, quantifying the percentage of predicted positive bindings that are true positives, was calculated using the precision_score function. Recall, indicating the proportion of actual positive bindings correctly identified, was computed using recall_score function. The F0.5 score is a variant of the F1 score where precision is weighted twice as much as recall. Similarly, auROC was calculated using the roc_auc_score function, providing an aggregate measure of the model’s ability to discriminate between positive and negative samples across all classification thresholds. auPRC, precision and recall values at various thresholds were obtained using the precision_recall_curve function and these values were subsequently used to calculate the auPRC.

Computational complexity and scalability of SMRTnet

SMRTnet contains a total of 208,191,155 model parameters. We assessed its computational complexity using an NVIDIA A800 (80 GB) GPU during both training and inference. Training the model using a fivefold CV process on the SMRTnet dataset, with a positive-to-negative sample ratio of 1:2, required approximately 48 h. GPU memory usage during training was about 14 GB with a batch size of 32. For inference, SMRTnet used approximately 4 GB of GPU memory with a batch size of 1. It took approximately 25 s to predict the binding score of a small molecule–RNA pair using the ensemble scoring strategy on a single GPU. This process could be substantially accelerated using the parallel ensemble scoring strategy, where the five models from fivefold CV were distributed across multiple GPUs.

Comparison of SMRTnet to existing computational methods

We evaluated SMRTnet and RNAmigos2 on each other’s test sets using their respective evaluation strategies and used the decoy evaluation task described in RNAmigos2 to benchmark SMRTnet against current field-leading computational tools. We used the RNAmigos2 model directly from its GitHub repository (https://github.com/cgoliver/rnamigos2/tree/3dab30ed6f5f63c328f32d2c6215ec14c572c2e2) without retraining.

Following the test set of SMRTnet and its evaluation strategy, we applied the SMRTnet model trained in each fold to predict binding scores for small molecule–RNA pairs in the corresponding test set and calculated the auROC values for each fold. For RNAmigos2, we generated RNAmigos2-compatible input pockets from PDB structures corresponding to RNAs in the test set of SMRTnet and predicted binding scores for each pocket–small molecule pair using RNAmigos2 to calculate the auROC values. In parallel, following the evaluation strategy of RNAmigos2 based on the test set of RNAmigos2, we calculated the auROC values for each binding pocket by comparing predicted binding scores between the pocket and both native and decoy molecules from different libraries. For SMRTnet, the binding score of a pocket–small molecule pair was computed by averaging the scores of all fragments within the pocket against the molecule. Decoys were obtained from three libraries: (1) the ChEMBL library, consisting of selected decoys from the ChEMBL database (n = 500); (2) the PDB library, which includes all ligands from the RNAmigos2 PDB dataset (n = 264); and (3) the ChEMBL + PDB library, a combination of the previous two libraries (n = 764). For RNAmigos2, we used the publicly available results provided by the authors on the Zenodo repository (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14803961)127 directly and visualized the results using Python (version 3.8.10), matplotlib (v.3.7.5) and seaborn (v.0.13.2) packages.

For decoy evaluation task, we generated a decoy molecule library for each small molecule in the SMRTnet dataset and evaluated the model’s performance on the basis of the ranking of the target molecule within its corresponding decoy library. Here, we used DecoyFinder to retrieve up to 30 decoys from the ZINC15 bioactive small-molecule library. These decoys were selected to be physically similar (for example, molecular weight, partition coefficient, hydrogen bonds donors, hydrogen bond acceptors and number of rotatable bonds) but chemically distinct (based on Tanimoto similarity) from the target molecule. Specifically, RNAmigos2 uses the RNA tertiary structure of the binding site and the corresponding target molecule with its decoy in the test set and ranks the target molecule within the decoy library on the basis of the predicted scores. RNAmigos predicts the ligand’s fingerprint on the basis of the RNA tertiary structure of the binding site and ranks the target molecule by computing the similarity between the predicted fingerprint and those of the target molecule and its decoys. AutoDock Vina, NLDock, RLDOCK and rDock treat the RNA tertiary structure of each target molecule in the test set as the receptor and the target molecule together with its decoys as the ligands and rank them on the basis of the scores generated by their respective scoring functions. SMRTnet calculates the binding scores between each RNA fragment and the target molecule or decoys using an ensemble scoring strategy. The final score for each molecule is obtained by averaging the binding scores across all RNA fragments. The target molecule is then ranked within its decoy library accordingly. Lastly, the ranking percentage is calculated by dividing the rank of the target molecule, determined by sorting the scores, by the total number of molecules.

For comparison, we retrained SMRTnet on a much smaller RNAmigos2 subset compatible with the SMRTnet training protocol by excluding nontherapeutically relevant small molecules and structures with fewer than 31 RNA residues. To prevent data leakage, we also built a data-leakage-excluded RNAmigos2 test set by excluding samples with identical multistrand binding sites and a maximum Tainmoto similarity threshold of 0.7 relative to the SMRTnet training data.

Binding-site identification of SMRTnet

We used Grad-CAM59 and the SmoothGrad algorithm128 to quantify the contribution of each nucleotide to the SRIs through backpropagation calculations. Specifically, Grad-CAM was used to generate saliency maps on the basis of gradient signals, while the SmoothGrad algorithm reduced noise and smoothed the saliency maps by averaging gradient signals across 20 perturbation rounds of the input. Higher gradient signals in the saliency maps indicate a greater importance of individual nucleotides in the binding process.

For an input SRI pair, the combined methods compute gradient matrices, where the RNA sequence encoder yields a 1 × 31 gradient matrix and the RNA structure encoder produces a 5 × 31 gradient matrix (later averaged to 1 × 31). Then, these are combined into a final 2 × 31 gradient matrix, where the first row represents RNA sequence-based gradient signals and the second row represents RNA structure-based gradient signals. In summary, given an input \(x\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{L\times D}\), the gradient \(g\left(x\right)\) for each encoder is calculated as follows:

$$g\left(x\right)=\frac{\partial {\rm{SMRTnet}}(x)}{\partial x}$$

(8.1)

$$\hat{M}\left(x\right)=x\odot \frac{1}{n}\mathop{\sum }\limits_{1}^{n}g\left(x+N\left(0,{\sigma }^{2}\right)\right)$$

(8.2)

Here, \({\boldsymbol{g}}\) represents the Grad-CAM algorithm, \(\hat{{\boldsymbol{M}}}\) represents the SmoothGrad algorithm, \({\boldsymbol{n}}\) is equal to 20, representing 20 rounds of minuscule Gaussian noise (\({\boldsymbol{N}}\left({\boldsymbol{0}},{{\boldsymbol{\sigma }}}^{{\boldsymbol{2}}}\right)\)) and \(\odot\) represents the operation of multiplication. To identify potential binding sites, we applied the Savitzky–Golay filter129 to smooth the discrete gradient signal and normalized the signals to the range of 0 to 1 using min–max normalization, thereby highlighting HARs in saliency maps.

Binding-site evaluation of SMRTnet

We quantitatively evaluated SMRTnet’s ability to identify RNA-binding sites by calculating the auROC value and the Pearson correlation coefficient between the gradient signals (from both RNA sequence and RNA structure) and the experimentally determined binding sites. For the auROC value calculation, nucleotides located within 10 Å of the ligand were label as 1 (positive) and all other nucleotides were labeled as 0 (negative)23; we computed the auROC value by comparing the gradient signals to these binary labels. For the Pearson correlation coefficient calculation, we measured the correlation between the gradient signals and the proximity to experimentally determined binding sites, where proximity was defined as 1 − normalized minimum distance from each nucleotide to any determined binding-site nucleotide. These evaluations were applied to five case studies, the test set of SMRTnet and two existing benchmarks (TE18 and RB19)57. For TE18, six entries were excluded: five entries involved magnesium ions (PDB 2MIS, 364D, 430D and 4PQV) or cobalt (II) ions (PDB 379D), commonly used to stabilize RNA structures, and one entry lacked a small molecule in the current PDB release (PDB 6EZ0).

Ablation study of SMRTnet

We evaluated the contribution of each encoder by setting the output embeddings of one or more encoders to zeros, thereby isolating their respective contributions to the model’s performance. Specifically, the output embedding of the following encoders was set to zero: (1) the RNA sequence encoder and small-molecule SMILES encoder; (2) the RNA structure encoder and small-molecule structure encoder; (3) the RNA sequence encoder; (4) the RNA structure encoder; (5) the small-molecule structure encoder; and (6) the small-molecule SMILES encoder. Additionally, we directly replaced the MDF module with a concatenation module to evaluate contributions of the MDF module (7). This approach enabled us to evaluate the impact of removing each component on the overall model performance.

MST assay

MST assays were performed using the Monolith NT.115 system (NanoTemper Technologies) with standard Monolith capillaries (NanoTemper Technologies, MO-K022). Cy5-labeled RNAs (10 nM), purchased from RuiBiotec (China), were folded in 1× assay buffer (8 mM Na2HPO4, 190 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA and 0.05%(v/v) Tween-20) by heating to 70 °C for 5 min, followed by slow cooling to room temperature at 0.1 °C s−1, as the RNA sample.

For the ‘binding check’ mode, small molecules were added into the RNA sample at the final concentration of 50 μM and incubated at room temperature for 30 min, as the small molecule–RNA complex sample. The red laser was selected on the basis of the Cy5 label of RNAs. The RNA sample and the small molecule–RNA complex sample were loaded into standard Monolith capillaries in four replicates and measured at room temperature by using 20% excitation power and medium MST power.

For the ‘binding affinity’ mode, small molecules were added into the RNA sample at the final concentration of 100 μM and then serially diluted twofold (15 times) with RNA sample. After the incubation at room temperature for 30 min, the 16 samples were loaded into standard Monolith capillaries and measured at room temperature using 20% excitation power and medium MST power.

For fluorescence intensity change after adding the small molecule into the RNA sample, SD-test was used to distinguish between small molecules as a function of changing fluorescence because of nonspecific effects or interaction with the RNA. The samples were mixed 1:1 with SD-mix (4% SDS, 40 mM DTT) and incubated at 95°C for 5 min, followed by detection of fluorescence intensity using 20% excitation power and medium MST power.

Data from the ‘binding check’ mode and SD-test were analyzed using MO.Control software (v.2.3) and data from the ‘binding affinity’ mode were analyzed using MO.Affinity Analysis software (v.2.3).

Cell culture

HEK293T and HeLa cells were purchased from Cell Bank, Shanghai Institutes for Biological Sciences, Chinese Academy of Sciences. Raji and Jurkat cells were purchased from Procell Life Science and Technology. HEK293T and HeLa cells were cultured in DMEM (Gibco) supplemented with 10% FBS (PAN-Biotech) and penicillin–streptomycin (Gibco) at 37 °C in 5% CO2. Raji and Jurkat cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium (Gibco) supplemented with 10% FBS (PAN-Biotech) and penicillin–streptomycin (Gibco) at 37 °C in 5% CO2. Mycoplasma contamination in all cultures was routinely checked using a Mycoplasma detection kit (Vazyme).

qPCR analysis

HeLa cells were seeded in six-well plates (200,000 cells per well) and treated with 0.1% (v/v) DMSO or candidate compounds (10 μM) for 48 h. Total RNA was extracted using the HiPure total RNA kit (Vazyme Biotech). RNA concentration and purity were assessed using a NanoDrop 2000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific), with an A260:A280 ratio between 1.8 and 2.0. For complementary DNA synthesis, 100 ng of RNA was reverse-transcribed using HiScript II Q RT SuperMix for qPCR (+gDNA wiper) (Vazyme, R223-01). qPCR was performed using ChamQ Universal SYBR qPCR master mix (Vazyme, Q711-02) on a QuantStudio 3 Flex real-time PCR system (Thermo Fisher Scientific), following the manufacturer’s instructions. Relative mRNA levels were calculated using the \(\varDelta \varDelta {C}_{t}\) method. qPCR primers and processed results are provided in Supplementary Table 7.

Western blotting analysis

HeLa cells were seeded in six-well plates (200,000 cells per well) and treated with 0.1% (v/v) DMSO or candidate compounds (10 μM) for 48 h. Total protein was extracted with RIPA buffer (100 μl per 200,000 cells). Approximately 20 μg of protein was separated by 12.5% SDS–PAGE, transferred to a PVDF membrane and blocked with 1× TBST containing 5% skim milk for 2 h. The membrane was incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary anti-MYC antibody (ABclonal, A19032, lot 3523042615; 1:1,500), followed by incubation at room temperature for 1.5 h with anti-rabbit IgG horseradish peroxidase secondary antibody (EASYBIO, BE0101, lot 80861011; 1:10,000). Alternatively, for GAPDH detection, the membrane was incubated overnight at 4 °C with 1× TBST containing 5% skim milk and then incubated at room temperature for 1.5 h with anti-GAPDH antibody (EASYBIO, BE0034, lot 80790311; 1:5,000). The membranes were detected using the enhanced chemiluminescence kit (New Cell & Molecular Biotech) and quantified using Fiji software. Processed statistical results are provided in Supplementary Table 8.

Cell proliferation assay

Cells were seeded in 96-well plates (2,000 cells per well) and treated with 0.1% (v/v) DMSO or candidate compounds (10 μM) for 48 h. For HeLa cells, cell proliferation was assessed using the MTT cell proliferation and cytotoxicity assay kit (Solarbio, M1020), following the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, after 48 h of incubation, the medium was replaced with 90 μl of fresh medium and 10 μl of MTT solution. The cells were incubated at 37 °C in 5% CO2 for 4 h. Subsequently, the solution was removed, 100 µl of DMSO was added and the plates were shaken at room temperature for 30 min. Absorbance at 490 nm was measured using a Spark microplate reader (Tecan). For Raji and Jurkat cells, cell proliferation was assessed using the cell viability/toxicity assay kit (CCK-8 kit) (FeiMoBio, FB29236-500), following the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, after 48 h of incubation, 10 μl of CCK-8 solution was added. The cells were incubated at 37 °C in 5% CO2 for 1 h. Absorbance at 450 nm was measured using a Spark microplate reader (Tecan). The relative cell proliferation was normalized to the absorbance of cells treated with 0.1% (v/v) DMSO. Processed statistical results are provided in Supplementary Table 9.

Cell apoptosis assay

Cells were seeded in 96-well plates (2,000 cells per well) and treated with 0.1% (v/v) DMSO or candidate compounds (10 μM) for 48 h. Cell apoptosis was assessed using the Caspase-Glo 3/7 assay system (Promega, G8091), following the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, after 48 h of incubation, 100 μl of Caspase-Glo 3/7 reagent was added. The cells were incubated at room temperature for 30 min. Luminescence was measured using a Spark microplate reader (Tecan). The relative cell apoptosis was normalized to the luminescence of cells treated with 0.1% (v/v) DMSO. Processed statistical results are provided in Supplementary Table 10.

MYC IRES luciferase reporter assay

The MYC IRES luciferase plasmid incorporates the MYC IRES sequence upstream of the Renilla luciferase gene in the psiCHECK-2 vector. HEK293T cells (approximately 80% confluent) were seeded in 60-mm dishes and transfected with 2 μg of the MYC IRES luciferase plasmid using jetPRIME (Polyplus, 101000027), following the manufacturer’s protocol. Cells were trypsinized and seeded into 96-well plates (2,000 cells per well) and treated with either 0.1% (v/v) DMSO or candidate compounds (10 μM) for 48 h. Renilla luciferase and firefly luciferase expression were measured using the Dual-Glo luciferase assay system (Promega, E2920), following the manufacturer’s instructions, and Renilla luciferase expression was normalized to firefly luciferase activity. Processed results are provided in Supplementary Table 11.

Quantification and statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted using GraphPad Prism 8 and Python (v.3.8.10), while visualizations, including bar plots, scatter plots, violin plots, radar plots and heat maps were generated with Python (v.3.8.10), matplotlib (v.3.7.5) and seaborn (v.0.13.2) packages. Statistical details are provided in the figure legends.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.